Co-written with Steph TJ

originally published on Jean-Hugues kabuiku Substack.

Our comprehension of the modern world is blurred by the erasure of the past. While researching the populist takeover of a coastal city facing the Adriatic during the volatile post-war period in Europe, we came across 20th century ideologies that explain a lot about the reactionary U-turn that not only our political parties have taken but also cultural institutions at large. As the western world has proven itself incompetent to deal with the COVID crisis, the response of its creative intelligentsia seems to be to withdraw into reactionary logic and go back to late 19th century technodeterminism, using almost the same dangerous talking points (sometimes coated in the politically correct language of neo-liberal identity politics).

If we seek to understand what’s at stake in the expression of the accelerationist direction that a wide range of cultural and political actors are taking, we need to go back to the start of the 20th century, when Italy came under the influence of “irredentism” & “Futurism”, the former being an expansionist ethnonationalist idea and the latter a technodeterminist ideology that helped build the aesthetic and ideological framework of Fascism. In this essay, we attempt to first build up a historical view of the political tensions of the eastern Adriatic, then unearth and situate the story of the 1919 nationalist takeover of Fiume (its Italian name), now Rijeka on the coast of modern Croatia1, by Gabriele D’Annunzio, the poet/war hero who seems to be kept as the secret of the 20th century. D’Annunzio and his allies had visions of establishing a modernist utopia in Fiume (Rijeka), but more realistically laid the groundwork for Mussolini’s coup d’etat in Rome. Mussolini would get inspiration from D’annunzio’s expansionist coup, which inspired his march on Rome.

There's been a link for a century now between technodeterminism and fascism. As the conversation around NFTs expands, with proponents talking about reshaping politics and Crypto Moguls doing it on the ground, we can see how ahistorical, technodeterminist utopian thinking continues to exploit vulnerable communities. This essay is an attempt to tell a story which is rarely told about the birth of fascism and futurism and its implications. Hopefully you will get a better view of southern east european history on the way, as we did in writing it.

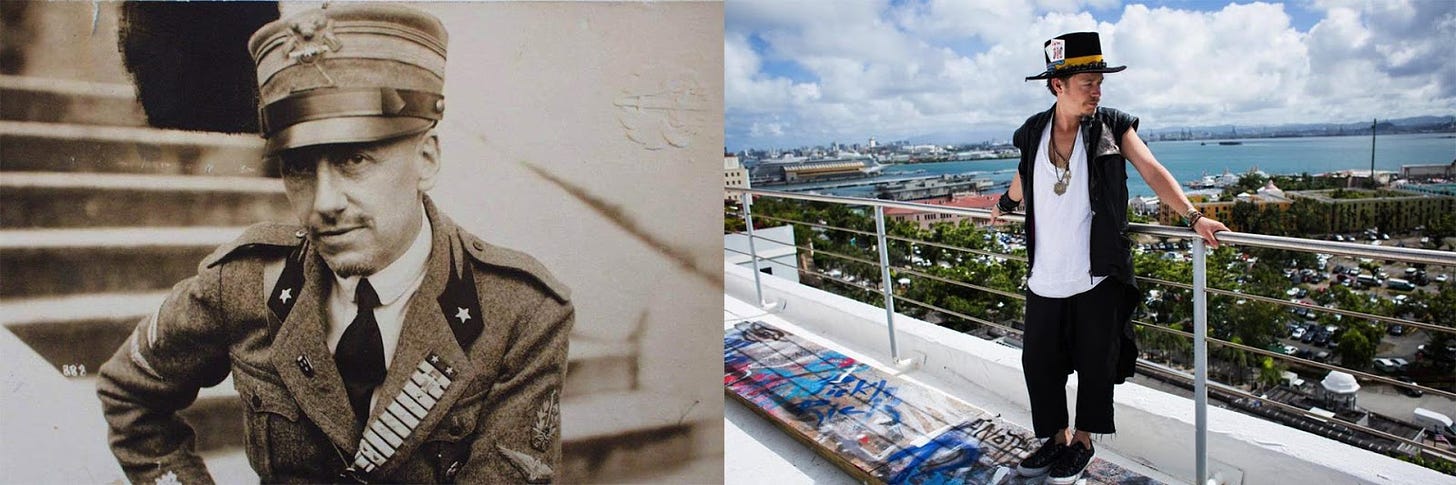

The Habsburg Empire

We have to begin with the Habsburgs (of the Austrian branch), to understand how Rijeka fell under the Italian peninsula’s sphere of influence. The Habsburg Empire, which existed in various forms for roughly 600 years before it was dissolved in 1918, formed a patchwork of territories joining speakers of Hungarian, Serbo-Croatian, Slovene, and more languages in semi-autonomous administrations under a sprawling Austrian dynasty2 3. When Austria was defeated in war in 1867, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise divided the lands of the Habsburg Empire in two regions, establishing the Dual Monarchy. From then on, the Austrian Empire took the northern and Dalmatian coastal territories, and the King of Hungary ruled historically Hungarian (or Magyar4) territory along with the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia from Budapest.

The Habsburg Monarchy and the Magyars feared bids for autonomy from subjugated ethnic groups, particularly southern Slavs who could potentially unify to consolidate power. Even with the limited autonomy granted in 1867 to the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, Hungary “[kept] Croatia in an imperialist strait-jacket” through governance and taxation, while official policies of “Magyarisation” around language and schooling reinforced control of the Croats. Historians of the period barely hide their pro-monarchy stance, by painting the Habsburgs like some enlightened rulers who used compromise to rule their possessions, when this story tell the tale of Machiavellian, divide-and-conquer methods of ruling.

How the city was shaped up to WWI

Fiume (Rijeka) came under Habsburg sovereignty in 1474, but was designated in 1779 as a “corpus separatum,” a city with semi-autonomous status, “directly subject to the Hungarian Crown… (that is, not as a part of Croatia).” Often in rivalry with Venice, Rijeka became part of Napoleon’s Kingdom of Italy briefly (1805-1809) under the Treaty of Pressburg. The city then belonged to the Napoleonic Illyrian Provinces, first within the province of Fiume, then as part of Croatia, but was given to the Austrian Empire during the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

As Fiume (Rijeka) fell under the domain of the Kingdom of Hungary within the Dual Monarchy in 1867, the Hungarian regime was invested in molding the demographics and economy of the lucrative port city to fit its interests. As AJP Taylor put it,

“Since the Magyars were too far from Rijeka to conquer it themselves (though there were 6,500 Magyars in 1910), they deliberately encouraged Italian immigration and gave Rijeka an exclusively Italian character.”

This took shape as the city developed in the latter half of the 19th century. The Italian mayor of Fiume (Rijeka) from 1872 to 1896, who had served previously in parliament in Budapest, enacted Hungary’s policies faithfully. A new rail line connected the two cities, while connections from Fiume (Rijeka) to Zagreb and Vienna were blocked. The modernization of the port drove rapid economic and population growth (largely Italian). In a reversal from an 1851 census reporting 12,000 Croats and 650 Italians, by 1910 there were 24,000 Italians and only 13,000 Croats. The disproportionate number of Italian schools (with several Magyar schools, and none designed as Croat) also signifies the assimilationist measures of foregrounding Italian language and norms in early education. [8]

One critical writer, Stjepan Radić, set out to document the experience of living under this system at the age of twenty. Misha Glenny reports,

“Budapest’s insistence on the sole use of the Hungarian language on the state railway was a perennial irritation to all Croats(..)Radić travelled the length and breadth of Croatia by train. Wherever he went, [he] would only speak Croatian to the conductors even though most of them were Hungarians. In a series of articles for the main opposition newspaper,(..)Radić described his adventures on the network and in particular the abuse and threats levelled at him by the staff. His odyssey culminated in a dramatic attempt by Hungarian railway workers to throw him off a speeding train.” [2]

Meanwhile in Italy, taking cues from the revolutions of 1848, various political actors, intellectuals and certain figures like Giuseppe Mazzini were grappling with the possibility and challenges of unifying the Italian peninsula. The peninsula was historically divided into several states, and since 1815, the northeastern part had been consigned to the Austrian Empire, while the Spanish Bourbons ruled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in the south. Emilio Gentile, a historian of the ideology of fascism, links Italy’s nascent nationalism to a drive for some sort of modernist renewal:

“From the Risorgimento on, the highest aspiration of the Italian patriots [was] to raise Italy to the level of the great modern nation-states, to form a national consciousness that would furnish a feeling of collective identity for the various Italian peoples who, though inhabiting the same peninsula, had remained separated from one another by profound political, social, and cultural differences virtually since the fall of the Roman empire. The founding fathers of a united Italy assigned the new State the task of liberating Italians from the habits of the “old man,” of turning them into truly “modern men,” as Silvio Spaventa put it.” [1]

Along with those ideas, “irredentism” emerged in Italy, a movement to claim “unredeemed” lands that were painted as belonging to Italy. The irredentist ideology was marked by argumentation about ethnic Italians (or, reductively, speakers of Italian) living in territories outside Italy’s rule, and accelerated by chauvinistic thinking about how Italy should be defined.

At the end of World War I, as Western powers redrew borders throughout the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, controversy descended on the city of Fiume (Rijeka). During the Paris Peace Conference of 1919-20, both Italy and the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes claimed a right to the city, depending on whether it was defined as the city proper, with its Italian-speaking majority, or the larger metropolitan area, with a majority of Croatian and Slovene speakers. Woodrow Wilson favored the Serbs, Croatians and Slovenes, probably as he was more assured of victory over Italy than any of the other imperial powers where border conflicts created opportunities for moral posturing. [8] Wilson’s logical inconsistencies and the turns in negotiations grew offensive enough to the Italian delegation that they walked out of the conference for weeks in April 1919, and a deadlock over Rijeka continued.

Fiume (Rijeka) had already been occupied by American, British, French and Italian troops by November 1918, and the Italian National Council formed the town’s provisional government. Although this transition was relatively seamless, the city was unprepared to independently face a growing currency crisis sparked by the dissolution of the Habsburg monarchy. While ineffectively managing the crisis at home, the Italian National Council fixated on annexation to Italy as the most profitable way to end their dependence on multiple unstable currencies. [8]

D’annunzio’s annexation of Rijeka

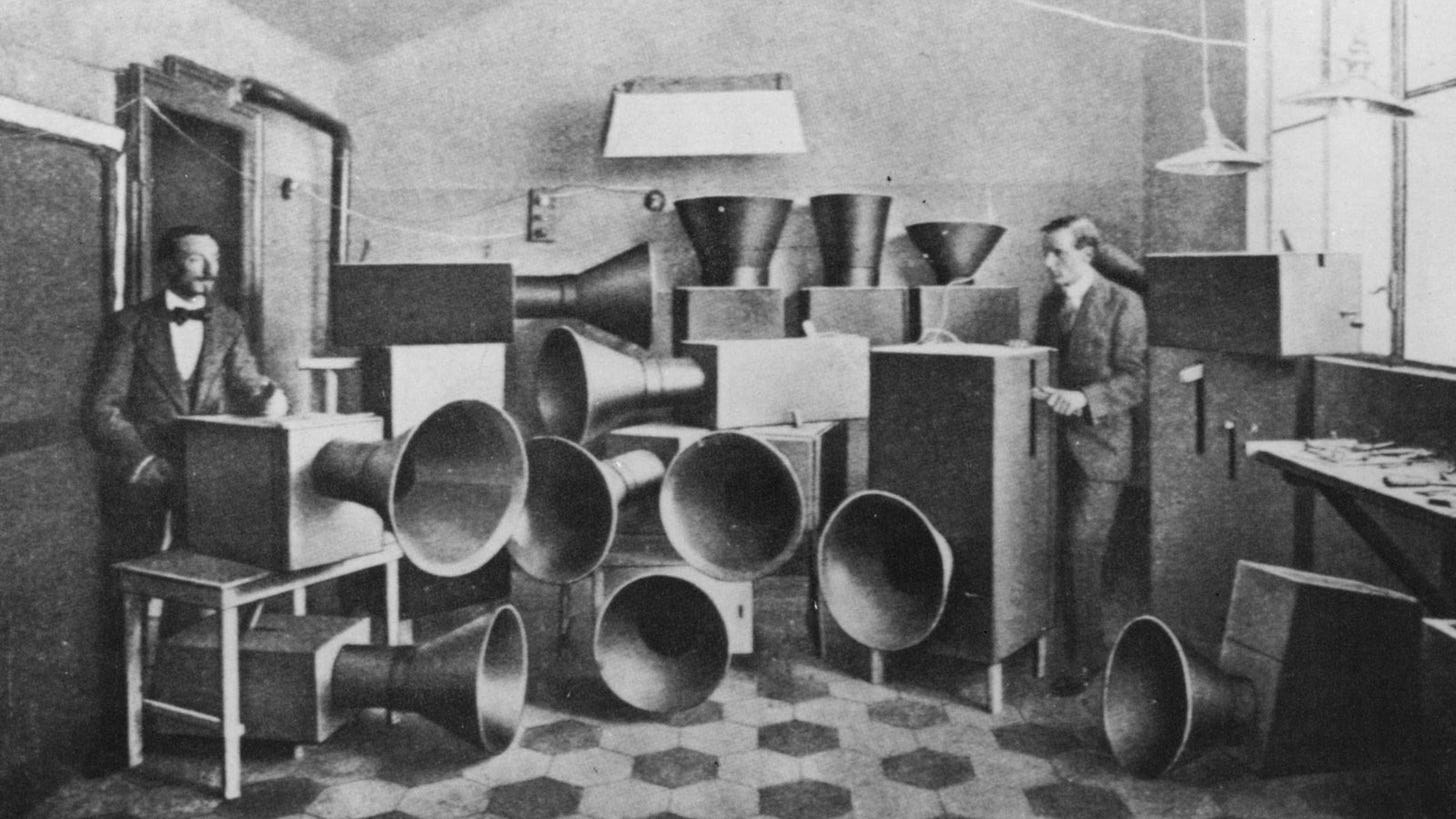

As the city gained a troubled spotlight in international politics, the Italian celebrity and increasingly nationalist poet, Gabriele D’Annunzio, placed himself in the center of attention. For context, D’Annunzio was initially well-known for his poetry belonging to the Decadent literary movement. He was reviewed internationally, becoming a household name in Italy:

“For almost thirty years not a week had passed without D’Annunzio’s name appearing in the newspapers, and for almost as long his name had been held before the public thanks to the undeniable fact that his works had been on display in the windows of every bookseller in Italy.” [11]

That said, his work sounds painfully shallow:

“Love lyrics, idylls on classical themes, patriotic dramas, and trashily plotted novels about supermen figures who are transparently the author himself: D’Annunzio’s output was formally varied, but the variety is skin-deep. Mummified at its centre lies an effigy of the poet himself. The hosts of characters in his collected works are, with few exceptions, shadows or silhouettes, denied individuation by the monotonous gaudiness of his language, styled to hypnotise and overmaster a reader.” [11]

D’Annunzio frequently drew from his own experience to write his romantic plotlines. His promiscuity only added to his notoriety, and served the image of his “virility”. As Barbara Stackman describes, “references to virility… pepper the writings of fascist intellectuals as though the word itself were proof of the writer's fascist credentials.” [9] She includes D’Annunzio in this pattern, citing his speeches in Fiume (Rijeka), where “nationalism and the rhetoric of virility are bound together.” D’Annunzio’s rhetoric and self-image of virility helped conjure up the machismo that would become a hallmark of future strongman dictatorships.

In tune with his taste for fame and power, after briefly holding a seat in parliament, D’Annunzio entered the military relatively late in life but pulled strings to quickly grab a cavalry position at the age of fifty-two. [5] With access to his choice of roles in the army, navy and airforce, his “daring exploits with aeroplanes and torpedo boats lifted his popularity to new heights; he became a full-blown national hero.” [11] This was in part due to his fluency with symbolism. As summarized generously by Michael Ledeen,

“D’Annunzio’s political effectiveness derived from a variety of elements of his own personality. His love affairs made him a symbol of virility, a crucial element for success in the Latin political world. His use of language and his oratorical skill made him an effective campaigner and an inspirational leader. His exploits in the war made him a national hero. His poetic skill, further, was of the utmost importance in his political enterprises, for he created the symbols of the new politics of the postwar world."

D’Annunzio took advantage of the turbulent political climate and vulnerability of Fiume (Rijeka) in 1919, arguably to further his own egotistical needs while representing the demand for annexation. In late August, a small group of Italian grenadiers, previously ordered to leave the city to calm a flare in local tensions, reached out to D’Annunzio (among other hardcore nationalists) for leadership in their plot to return and reclaim the city for Italy. Assuming command of some 200 recruits, D’Annunzio converted more troops from Italian army personnel along the march from Ronchi, including some Arditi (“The Daring”) special forces. By the time D’Annunzio and around 2,000 followers reached Fiume (Rijeka), they were essentially ushered into the city, without a shot fired. D’Annunzio’s fame definitely played a part in this, but so did the advance coordination from inside and outside the city and some confusion in the defending ranks. Since irredentism was by then a strong political force within the Italian army and petty bourgeois circles, the Italian generals were unsurprisingly more willing to turn over the city than intervene against their colleagues.

This scene was a prototypical expansionist intervention under the pretense of claiming “rightful” territory, to be replicated by states throughout the next century. It also functioned as a first military provocation in the middle of international tensions, where D’Annunzio’s campaign was the “casus belli” for the Italian invasion of the key port city.

As we have spelled out above, the fulfillment of this mission owed a lot more to the economic interests of the local population, and its existing occupation by Italian and other Allied soldiers, than to any military prowess on the part of D’Annunzio. We can also look to the parallel development of Italian Futurism to understand how the expansionist project gained additional momentum.

Futurism’s links with D’Annunzio and fascism

Futurism has a well-deserved reputation for its entanglement with early fascism. Early in the 20th century, Italy and Europe faced a “crisis of civilization” in the search for a new system of values after the fall of Catholic empires and the development of industrialism. The avant-garde poet F.T. Marinetti and his cohort entered the conversation with their disruptive platform to forget all former values, even forget history, and strive only for youth, speed, violence, and technological progress. A section of Marinetti’s 1909 Futurist Manifesto illustrates the sense of accelerationist mania:

“6. We stand on the last promontory of the centuries! [...] Why should we look back over our shoulders […] We already live in the absolute, for we have already created velocity which is eternal and omnipresent.

7. We intend to glorify war—the only hygiene of the world—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of anarchists, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and contempt for woman.

8. We intend to destroy museums, libraries, academies of every sort, and to fight against moralism, feminism, and every utilitarian or opportunistic cowardice.”

The manifesto is replete with ahistorical delusion, sacrificial militarism, anti-intellectualism, and anti-feminism. Bejamin Noys, in “Malign Velocities: Accelerationism and Capitalism,” points out the misogynistic, anti-humanist underpinnings of the Futurist ideal of “masculine and protofascist mastery over nature by technology and acceleration.”5

The mechanization of the human body and experience discards femininity or anything that doesn’t serve technical or capitalist notions of progress. If the implicit links to the fascists’ genocidal outlook seem clear today, they were also apparent at the time: the prominent liberal philosopher and historian Benedetto Croce wrote in 1924, “To anyone with a sense of historical connections, the ideal origins of fascism are to be found in futurism.” [1]

Beyond this, Futurists overtly helped shape the image of Italian Fascism:

“[T]he principal exponents of futurism were among the founding fathers of the fascist movement and firmly adhered to the totalitarian regime, actively collaborating in the creation of its culture and the diffusion of its ideology” [1]

Gentile names several artists, architects, and experimental theater promoters who “faithfully and passionately contributed to the construction of the symbolic universe of fascist religion.” Artists of this stripe “participated in fascism, it must be emphasized, rather than simply adhering to it. For the involvement of futurism in fascism was not simply an external act of joining a political movement, but an active and self-aware collaboration in elaborating the movement’s culture and political style.”

D’Annunzio’s ideation about technology, youth and the future of Italy echoed Futurist visions, which attracted the movement’s adherents to the city he held in 1919-20. Like the Futurists, D’Annunzio combined worldly events with sacred references and symbolism [5]. Even further, Noys notes how D’Annunzio captured the Futurist obliteration of human need with his “personal motto ‘per non dormire’ (‘In order not to sleep’).”6 Underlining the philosophical similarities, the critical poet Gian Perio Lucini discussed Futurism in 1913 as an “exacerbated D’Annunzianism.” [via Gentile] In fact, D’Annunzio undoubtedly cast an influence on Marinetti, who wrote on him for years as a journalist [4].

Just as Futurists, including Marinetti, visited D’Annunzio’s outpost in Fiume (Rijeka), some of the participants in the takeover of Fiume (Rijeka) got further involved in Fascism in Italy. As Reill writes, “many (but not all) of those who accompanied D’Annunzio to Fiume later joined Mussolini’s Fascist squads.” More broadly, as voting rights expanded along with the speed and scope of press coverage, Mussolini inherited a new view of how to cynically/sadistically manipulate mass politics, borrowing symbols and mottoes on top of recruits from D’Annunzio’s militia. As Pankaj Mishra put it in his article “The Globalization of Rage” for Foreign Affairs:

“D’Annunzio and his cadres dressed in black uniforms adorned with a skull-and-crossbones insignia. They spoke obsessively of martyrdom, sacrifice, and death(..) he introduced the stiff-armed salute that Adolf Hitler would later adopt.”

NUI Galway professor Mark Phelan recalls an instance when Mussolini helped D’Annunzio with an arms smuggling operation for the IRA, in the context of his parody of the League of Nations, a movement on behalf of the oppressed people of the world called the “League of Fiume.”

“Mussolini, as leader of the growing Fascist movement, had access to influential elements within the military. Armed with written instructions from D’Annunzio, [IRA representatives] travelled to meet the future dictator in Milan. Already keenly interested in the Irish Question, Mussolini enthused about the proposed gunrunning venture. Indeed, in a written reply to D’Annunzio, he promised not only to broker a meeting with the military but also to finance any resulting arms shipment to Ireland. Fulfilling the first part of this commitment, Mussolini helped to arrange a meeting at the War Ministry in Rome.”

This fits the picture of their connection, as they were both collaborators and direct rivals. For example, “after the war (..) D’Annunzio was mooted in proto-fascist circles as a contender for national leadership, (..) and Mussolini rewarded him lavishly to stay out of politics. (‘Two things can be done with a bad tooth,’ he quipped. ‘Pull it out or fill it with gold.’)” [1]. Similarly, here it seems like Mussolini was supporting D’Annunzio but also wanted to softly get rid of him by shipping him to the Emerald Isle.

What can we learn about the Italian Regency of Carnaro?

We can see the outgrowth of all of these influences - the joining of ethnonationalism, accelerationism, and aestheticization of politics a la Futurismo in the way D’Annunzio governed his project in Fiume (Rijeka). The spectacle of the city’s takeover was pronounced from the beginning, with D’Annunzio arriving in a red Fiat filled with flowers (fittingly, as Fiat had sponsored interventionism in Italy), then unraveling a symbolically loaded red, white and green military banner over the balcony where he gave the first of his many speeches to a local crowd [4, 5]. His speeches from the balcony became a regular ritual that kept the local populace engaged in the ideology of the takeover [11], while the proliferation of flags throughout the city cemented the Italianisation agenda of D’Annunzio and his followers. The Italian National Council requested and received thousands of flags from the Italian military, then commissioned local tailors to produce more [8]. Official policies mandated the use of Italian language and punished insufficient shows of allegiance, while “at least two waves of vandalism against Croatian signs and storefronts beset the town in 1919 and 1920, with locals shattering public emblems of the city’s prior multilingualism.” [8]

In the summer of 1920, when a plebiscite threatened to derail the Italian annexation, the votes getting close to confirming a conciliatory offer from Italy to just protect the separated status of the city, D’Annunzio stopped the vote, ousted the local administration, and drafted a new constitution that he would use to declare the city as the Italian Regency of Carnaro. The “Charter of Carnaro” empowered trade organizations in a form of corporatism, introduced universal suffrage, and promoted music as a substitute for moralism in the legal code. In addition to the libertarian flavor of its new laws, the city seemed to be characterized by festive excess. But in this sense, as Ledeen advises, “D’Annunzio did not create a new world overnight in Fiume, but rather arrived upon a scene highly congenial to his particular tastes and talents.”

Just over a year after D’annunzio entered the city, the Treaty of Rapallo designated Fiume (Rijeka) as a Free State. Once again, D’Annunzio refused to accept this outcome and declared war on Italy. A brief battle over the Christmas holidays of 1920 ended his reign, and closed the chapter of the Italian Regency of Carnaro, but the poet-demagogue’s methods were copied horrifically over the next century. Notably, there remained separate strands of Autonomists, who formed their own party that won in the first election against a pro-Italian contingent in 1921. But Italian Fascists then took the city in a coup d’etat in 1922. This time period of growing fascist tendencies incidentally also saw some of the first committed anti-fascists, like the Arditi del Popolo, an offshoot of the specialized unit that had helped bring D’Annunzio to power. Ultimately, though, fascist Italy claimed the city again when Mussolini enacted a treaty with the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes as Prime Minister in 1924.

Our sources mention two possible motivations for D’Annunzio’s doomed, last-ditch 1920 declaration of war on Italy: his egomania, and his apprehension that Italy wouldn’t adequately uphold the independent status of Fiume [4,5,10]. Still, the war provocation and subsequent attack seem more in line with D’Annunzio’s original plans, to prompt Italy to subsume the city-state. Either way, his actions are comparable to false flag tactics that have been used around the world to precipitate territorial invasions.

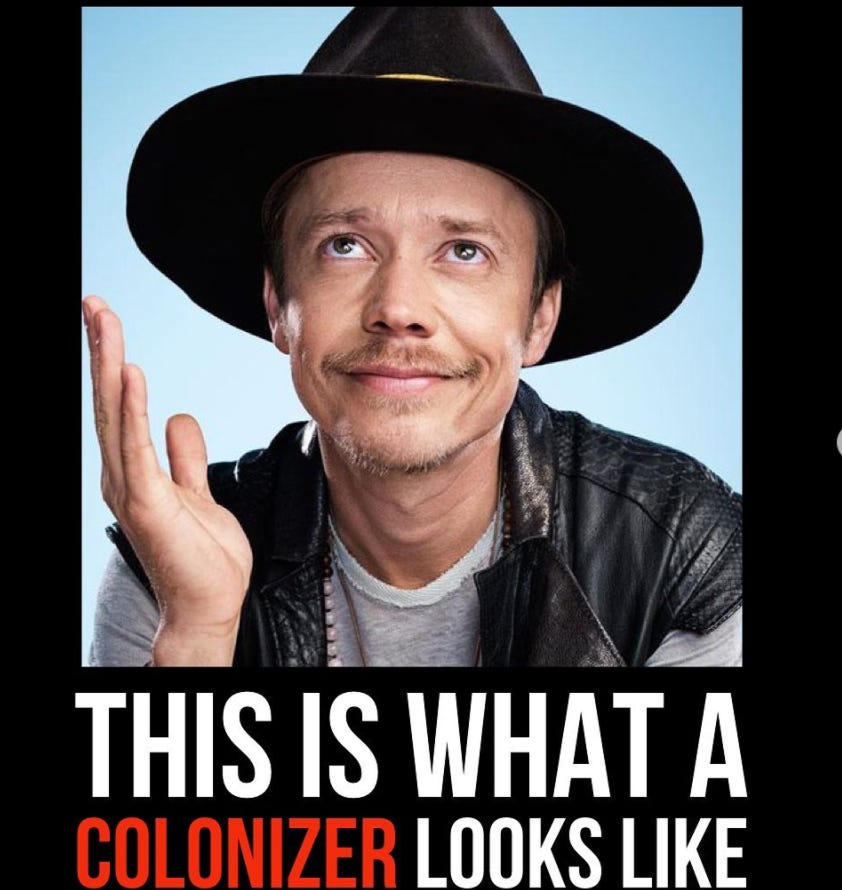

Brock Pierce modern-day D’annunzio ?

D'Annunzio and Crypto giant Brock Pierce's story share similarities at such a level that we are coining him as the modern day D'Annunzio. He’s literally at the spearhead of a Crypto-Colonizers movement in an old Habsburg7 territory.

The US government imposed austerity politics in his colonial territory of Puerto Rico, which translated into the closure of hundreds of hospitals and schools, and privatization of its public resources which results in the territory losing half a million residents:

“With around three million residents today, the U.N. expects Puerto Rico's population to plummet to 1.2 million by 2099. Residents are fleeing paradise… As the debt collectors leave Puerto Ricans with no choice but to pack up and go, the U.S. and Puerto Rican governments have collaborated to attract wealthy settlers to the colony.”8

When we read about Brock Pierce’s interest in Puerto Rico, we can’t help but think about D'Annunzio, a charismatic leader helped by the ideology of technodeterminism in taking over a small colony with his followers and sugar-coating it behind the veil of “Philanthropy.”

Brock Pierce's interest in the Island lies in the fact that the U.S. and Puerto Rican governments have offered large tax incentives to independent investors.

Neil Strauss for Rolling Stone recalls in his article the Hippy King, “He’s also co-founding a bank in Puerto Rico, and plans to open both an eco-resort in the island’s famous surf spot Rincón, and a large cluster of residences in nearby Mayagüez.”

In 2011 the local government introduced a law known as Act 22, which promises a zero personal capital gains tax to U.S residents combined with Act 20—which charges corporations just 4 percent in capital gains tax for export services in order to attract wealthy American settlers.

Strauss quotes Pierce, “We’re going to rebuild Puerto Rico with money that we saved from the IRS in a Robin Hood fashion,” he says with a smirk. ”9

In this article we also find his link with Steve Bannon, who he hired for his video game real-money trade company: “In 2005, he hired a former Goldman Sachs banker to help with acquisitions and financing. His name was Steve Bannon, Donald Trump’s future chief strategist.”

We were honestly only half-surprised as he would be later on adopting the Dark Enlightenment ideology while at the white house.10

Here is his view on Crypto: “You can see the forces that are aligned to take advantage of it. Every smart person that I admire in the world, and those I semi-fear, is focused on this concept of crypto for a reason. They understand that this is the driving force of the fourth industrial revolution: steam engine, electricity, then the microchip – blockchain and crypto is the fourth. There’s going to be a war for control for this.”

The futurist manifesto and its relationship with technology, filled with the need to erase history and a machismo aesthetic of the conqueror of machines, seem to heavily influence these tech moguls — Technodeterminist circles where white-cismales are overly represented, spreading a gospel on how technology is going to liberate us or make the music industry more egalitarian, draw so much from Italian Futurist writing that it’s just scary.11

As Helen Hester put it in Xenofeminism,12

“Technology is as social as society is technical. Technologies, then, need to be conceptualized as social phenomena, and therefore as available for transformation through collective struggle […]. Technological change is a ‘process subject to struggles for control by different groups,’ the outcomes of which are profoundly shaped by ‘the distribution of power and resources within society.’” [3]

It’s then justifiable to be concerned when someone who says that they want to help democratize the blockchain only invites white people. The Agenda seems pretty clear.

The Torpedo got replaced by the blockchain.

As media like XLR8R launch their NFT Marketplace for Electronic Music, we can already see the accelerationist model that one side of the “scene” is a part of.

#BLM am I right?

It also bears the question: if NFTs are supposed to materially support everyone, why are the discussions and initiatives on those technologies so white? One can notice some representation in crypto-art, in particular Black male artists, but it doesn’t get past tokenism. Crypto-art is an opportunity to make a quick buck, while it has momentum, but this doesn’t constitute a way to soothe financial hardship, for the biggest numbers. If there is any, cause you will have a pattern of actually wealthy black producers engaging in this, as minting NFT costs can drastically differ depending on the time you do it13, could be 58$ or up to 200$, literally a gamble that also has an unreasonable ecological cost.

I don’t leave the possibility that if not in their language14, with their actions they are showing their total disinterest with mutual aid and/or political struggle to improve the material conditions of the less fortunate members of their “community.” They overlook the fact that if they don’t participate in the struggle, they will be held accountable by their community when the wind changes direction. Also, they are shooting themselves in the foot as they are participating in a white supremacist exclusionary trend that will result, in the “best case” scenario in the status quo and in the worst case, more austerity politics and the stripping off of what is left to wealth fare as there will be this narrative of how this NFT15 can be a get rich scheme for artist. The new “Oh you struggling finding a job, have you tried learning to code?”

You can follow the campaign against act60 in Puerto Rico, a tax law that incentivizes wealthy people to move to Puerto Rico and take control of land, exports, monuments, and natural resources. https://www.instagram.com/abolishact60/

You can check the Expropriate Deutsche Wohnen and Co campaign a referendum to expropriate and socialize the apartments of mega-landlords in Berlin.

We also want to thank @drmathys_ for his help with editing & contribution on the NFT part of the article

Support independent research effort and critical effort against technodeterminism by joining the substack https://jeanhugueskabuiku.substack.com/

The VOL II of this essay is here

References

Main references are cited with bracketed numbers. Footnotes refer to the comments/urls below

[1] The Struggle for Modernity Nationalism, Futurism, and Fascism by Emilio Gentile

[2] The Balkans: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers, 1804-2012 by Misha Glenny

[3] Xenofeminism by Helen Hester

[4] Gabriele D’Annunzio16 by Lucy Hughes-Hallet

[5] The First Duce: D’Annunzio at Fiume (1977) by Michael Ledeen

[6] Futurism: An Anthology by Lawrence Rainey, Ms. Christine Poggi, Laura Wittman

[7] Malign Velocities: Accelerationism and Capitalism by Benjamin Noys

[8] The Fiume Crisis: Life in the Wake of the Habsburg Empire by Dominique Reill

[9] Fascist Virilities: Rhetoric, Ideology and Social Fantasy in Italy by Barbara Stackman

[10] The Habsburg Monarchy, 1809-1918: A History of the Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary by A.J.P. Taylor

[11] The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Fron by Mark Thompson

Additional readings were also helpful:

Fascist Modernities: Italy, 1922-1945 by Ruth Ben-Ghiat

Italian Futurism: Politics and the Path to Modernism by Antonio Gramsci

The Risorgimento and the Unification of Italy by D Beales and EF Biagini

Austria, Hungary, and the Habsburgs: Central Europe c.1683-1867 by RJW Evans

The Civic Foundations of Fascism in Europe Italy, Spain, and Romania, 1870-1945 by Dylan Riley1

For the rest of this article, “Rijeka” refers to the city in modern times, and we will use “Fiume (Rijeka)” for the historical city. Both “Rijeka” and “Fiume” mean “River,” in Croatian and Italian respectively.2

We will generally aim to keep a distinction between ethnic groups, based on religion and cultural tradition, and language communities: “Denoting an ethnic or national identity in the eastern Adriatic based on language use is an impossible and historically incorrect exercise.” [8]3

About the empire’s economic structure: “The Habsburg lands were a collection of entailed estates, not a state; and the Habsburgs were landlords not rulers - some were benevolent landlords, some incompetent, some rapacious and grasping, but all intent on extracting the best return from their tenants.” [10]4

“Magyar” is the Hungarian word for a Hungarian person, as well as the language. Here we are using the term to denote ethnicity, while “Hungarian” in historical context refers to regions or citizens of the Kingdom of Hungary. [10]5

Noys continues, “The contempt for woman indicates the usual armoured trope of erecting the hard, phallic and mechanized male body over and against the feminized: soft, liquid, and organic...Marinetti’s misogyny also opens on to a general anti-humanism – the cult of speed is one that bursts apart the limits of the human.”6

Noys adds, “It might also stand as the motto for contemporary capitalism, which, as Jonathan Crary has noted, declares war on sleep as one of the few residual and non-productive human activities.” 7

of the Spanish branch8

https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-horrific-colonialist-costs-of-puerto-rican-us-statehood9

https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/brock-pierce-hippie-king-of-cryptocurrency-700213/ 10

https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/02/steve-bannon-books-reading-list-214745/11

let’s take Marinetti’s explanation of his political movement from his text “The Futurist Political Movement,” published in 1913, when he writes a long list of what his political movement will defeat: “The cult of museums, ruins, and monuments, The obsession with culture, Academicism” — isn’t it what, “let’s use NFT for art market” enthusiastsare fighting against?12

here Hester is citing Shulamith Firestone’s influential, “contentious” 1979 manifesto The Dialectic of Sex.13

It also depends on the platform you use14

cause it’s not really a good look to be a greedy technodeterminist capitalist15

or whatever new crypto sensation based on blockchain16

although the book presents unique facts and anecdotes, we avoided referring to it otherwise as the cover shrouds D’annunzio in an Italian flag, and the text glamorizes its subject much more often than considering his role in accelerating fascism because “disapproval is not an interesting response.”